In 1976, Schindler criticized of the EIA system in a way that can still be seen in the practice today; EIAs can be used to silence eco-freaks, implicating that once a project get accepted, further social or environmental impacts won’t be significant. But what happens if an EIA isn’t done properly? The still ongoing Val-Jalbert case study, in the Lac-St-Jean region of Quebec, illustrates adequately this concept.

Left: 2010, Ouiatchouan waterfall in the historic Village of Val-Jalbert. Right: 1930, Family Gagnon from Val-Jalbert, an old pulp mill site in the early twentieth century. Photo credit: BANQ

The project consists of a small hydroelectric central and a 37,5 m long dam located upstream of the Ouiatchouan waterfall, inside the patrimonial site of the historic Village of Val-Jalbert. The spectacular 72m high waterfalls is the main attraction of the site, which is the second touristic attraction of the region.

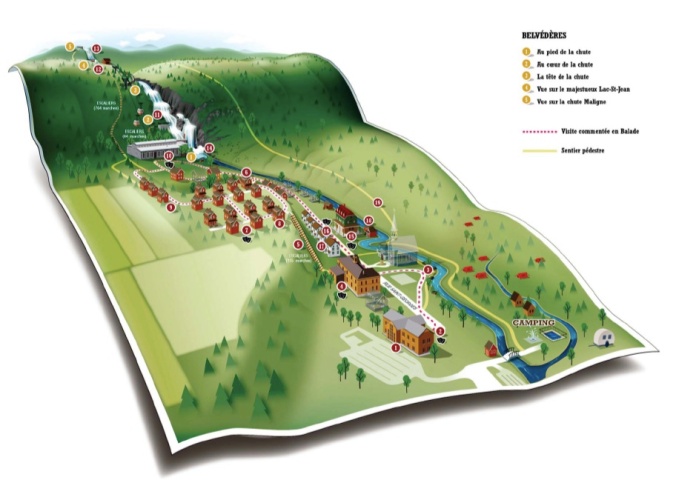

Aerial view of the historic Village of Val-Jalbert. Yellow dots represent viewpoints on the waterfalls. Image credit: http://www.valjalbert.com

Questionable choices of profits

For each million of economic benefits that the project will induce in the region, the project will cost 4 millions to the Quebec collectivity, because the Quebec is in energetic surplus. Martine Ouellet, from the Parti Québecois, decided to stop six out of seven small hydroelectric central, excluding Val-Jalbert. Their main argument is that the go for the project was already delivered. Amir Khadir and François Legault, respectively from Québec Solidaire and the Coalition Avenir Québec, denounce this economic incoherence, based on the work of the Parliamentary Committee on energy surplus. Could these gigantic economic losses (80 billions dollars in 20 years) be invested in the region to build new sustainable project instead of demolishing existing one? Could alternatives be considered?

Biased Environmental Impact Assessment

Part of the answer why these questions weren’t addressed concern the possible conflict of interest that surrounds the Val-Jalbert project. Indeed, the EIA was conducted by BPR and Dessau, the same firms that will supervise the construction site, which supposes a major conflict of interest while the engineering firms don’t have any advantage to state that the project doesn’t have good standards in environment.

During the touristic season, an esthetic daily flow of 7 m3/s is projected. This represents the half of the actual river flow. During the night and the winter, the flow will be equivalent to a standard domestic water heater. The EIA report state that no valuable ecologic component (VEC) assessment was possible on the river section that will be dried out (1km long), because the accessibility was dangerous. The EIA consequently based its prediction on literature, while numerous fisherman (including Innu testimony from the Pekuakamiulnuatsh Alliance), witness of a rich diversity of fishes, especially a healthy 700-800g brook trout population.

Average daily flow simulation of the Ouiatchouan waterfalls. Pale blue: actual flow. Dark Blue: projected flow. Green: esthetic projected flow for touristic season. Graphic credit: BAPE 2012.

Social unacceptability

Léger Marketing did a regional survey in late January. The results show that 51 % of the citizens are opposed to the project while 39 % support it (10 % undecided). An interesting point is that 61 % of respondent wish the cancellation or suspension of the already started construction work for the benefits of a public consultation. The project raises controversy because of the intangible cultural appropriation from the population. It also deals with the unhappy Innu community from Mashteuiatsh. Without consulting the community, the Band Council sold the Natissian territory for profits that will not return to the Mashteuiatsh community. Therefore, Innus aren’t able to access the site anymore, Val-Jalbert is only opened to tourists. They are mainly against the project and they triggered a Band Council referendum.

Despite the construction work being started since February, members of the opposition committee for the safeguard of the Ouiatchouan river of Val-Jalbert and the Pekuakamiulnuatsh Alliance installed a camp near the site. Will the bias EIA be able to break the social unacceptability? The story is to be followed.

* This blog post was written March 6th.

References

Bureau d’audiences publiques sur l’environnement (BAPE), 2012, Projet de mise en valeur hydroélectrique de la rivière Ouiatchouan au village historique de Val-Jalbert – Rapport d’enquête et d’audience publique – Rapport 289, Quebec, 102 pages.

Fondation Rivière, 2013, Actions Val-Jalbert, http://fondationrivieres.org/agir-pour-sauver-val-jalbert/

Leclerc, V., 2013, Val-Jalbert – Site patrimonial en péril, Huffington Post, http://quebec.huffingtonpost.ca/viateur-leclerc/val-jalbert-site-patrimonial-en-peril_b_2696912.html

Rioux, M., 2013, Val-Jalbert, tout faire pour boquer ce projet insensé, Greenpeace, http://www.greenpeace.org/canada/fr/Blog/val-jalbert-il-faut-tout-faire-pour-bloquer-c/blog/44032/

Shields, A., 2013, Le projet de Val-Jalbert divise la région, Le Devoir, http://www.ledevoir.com/environnement/actualites-sur-l-environnement/371481/le-projet-de-val-jalbert-divise-la-region

Shindler, D.W., 1976, The Impact Statement Boondoggle, Science, Vol.192, no. 4239, p.509.

Société de l’énergie communautaire du Saguenay-Lac St-Jean, 2013, Le projet de Val-Jalbert, Les projets en développement, http://www.energievertelsj.ca/fr/16/Le-projet-de-Val-Jalbert/

Société Radio-Canada, 2013, L’opposition fait front commun contre le projet de minicentrale de Val-Jalbert, Huffington Post, http://quebec.huffingtonpost.ca/2013/02/15/opposition-front-commun-val-jalbert-quebec-solidaire-caq_n_2695939.html

Société Radio-Canada, 2013, Minicentrale de Val-Jalbert: les opposants affirment que l’étude d’impact a été baclée, http://www.radio-canada.ca/regions/saguenay-lac/2013/02/26/007-minicentrale-opposants-etudes.shtml