Water and its availability in Peru and the world

Since ancient times, access to water has become a source of power and/or the origin of great conflicts. This is mainly because water is a vital but scarce resource. Of the 1,400 million km3 of available water, only 2.5% constitutes fresh water, of which only 0.7% is available for human use (UNEP 2010).

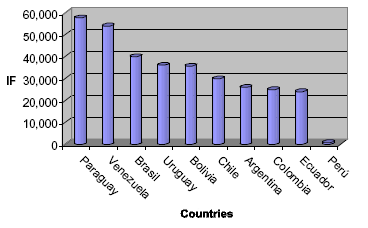

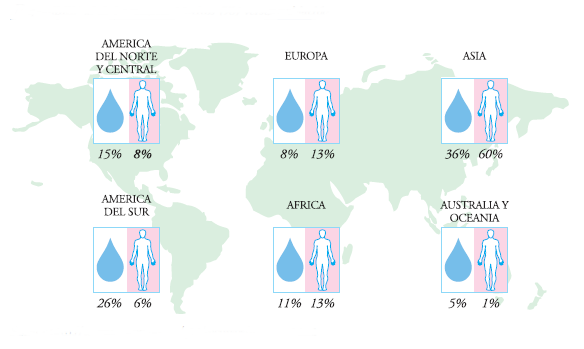

To complicate matters even further, water resources are not distributed proportionally among the population. There are continents like Asia with 60% of the population and only 36% of water resources, while others like South America with only 6% of the world’s population, enjoy the 26% of water resources.

Water availability (%) versus population

Source: Fernández-Jáuregui (1999)

However, there are some important disparities in South America as illustrated in the Figure below. For instance, Peru is one of the countries with the lowest availability of water resources, and this can be seen when comparing Falkenmark[1] indicators (IF) from the various South American countries (Guevara 2008).

Source: Guevara (2008)

Given this reality, it is not surprising that a lot of environmental conflicts exist in Peru (Defensoría del Pueblo 2007), many caused by the use of water, including the emblematic Conga project.

Conga project

Yanacocha[2] is one of the largest mining companies in Peru. The Yanacocha mine in the department of Cajamarca, which is the second largest gold mine in the world (Yanacocha 2010), runs operations since 1992. Among the main exploration projects of Yanacocha is the Conga project.

The Conga project comprises the removal of 11.6 million ounces of gold and 3.1 billion pounds of copper, representing an investment of $ 4.8 billion for 19 years, becoming the largest investment in the history of Peru.

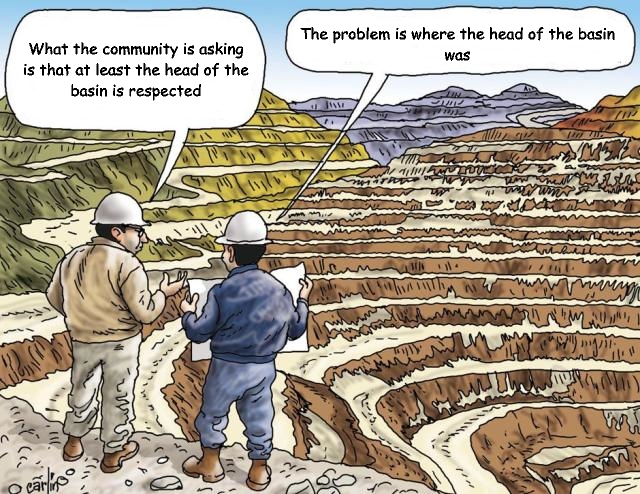

The project is located at the headwaters of several rivers basin and its design considers emptying four lagoons, two to extract minerals (Perol and Mala lagoons) and two to store tailings (Azul and Chilca lagoons); Yanacocha instead proposes the construction of water reservoirs.

The projected loss of these lagoons has made large sectors of the population of Cajamarca reject the Conga project because it would compromise the basin´s head that provides water to the region.

To better understand this rejection we must also consider that the relationship between Yanacocha and the local population is quite damaged, because since the mine began to operate in Cajamarca there have been several incidents (poor communication, arrogant attitude from the company, unfulfilled commitments, mercury spills) that “have engendered resentment, fear and distrust towards the company” (Elizalde, 2009).

This discomfort is reflected in numerous protests and strikes, which have confronted the people of Cajamarca with the police, leaving several deaths and injuries as a toll.

EIA Assessment Process

The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) of this project (Knight Piesold, 2010) was completed in February 2010 and in October of the same year was approved by the Ministry of Energy and Mines.

However, in November 2011 the Ministry of Environment (MINAM) prepared a report with comments on the EIA (Ministerio del Ambiente 2011). According to this report, “the Conga project will transform in a significant and irreversible way the head of basin” since “several ecosystems will disappear, while others will be fragmented, so that the processes, functions, interactions and ecosystem services will be affected irreversibly”. Furthermore, the construction of reservoirs against the removing of the lagoons does not mitigate the impact, only compensates “the water supply service, leaving aside the compensation of the lost environmental services“.

When this report was made public, the Minister of Energy and Mines said it was “alarmist”, which led to the resignation of the MINAM´s Vice Minister declaring that the government does not have a “right strategy to tackle social conflicts”.

At the end of 2011 an indefinite strike in Cajamarca against the Conga project began which brought down the Prime Minister and his cabinet. The new Prime Minister convened an international expert opinion to evaluate the EIA (Rubio et al 2012). This expert opinion concluded that the EIA meets all the technical requirements. However, it proposed some recommendations to evaluate alternatives for tailings’ storage and thus save Chilca and Azul lagoons.

Currently, the Conga project is temporarily suspended due to the company’s decision and the people are guarding the lagoons to prevent the recommencement of the project.

Source: Diario16.com.pe (Noviembre 26, 2011)

Source: Diario16.com.pe (Noviembre 26, 2011)

I leave you with a cartoon that satirizes an unfortunate situation in this regard.

Translated from: http://celendinlibre.wordpress.com/2012/04/17/pronunciamiento-ong-oxfam-se-pronuncia-respecto-a-caso-minas-conga/

Here is a video produced by the European television where the Conga Project problem is analyzed:

Bibliography:

- Defensoría del Pueblo. 2007. Los Conflictos Socio-ambientales por Actividades Extractivas en el Perú.

- Diario16.com.pe. Noviembre 26, 2011. De lagunas a desmontes. http://diario16.pe/noticia/12046-de-lagunas-a-desmontes

- Elizalde, B. 2009. Reseña de las Relaciones de Newmont con la Comunidad: Mina de Yanacocha, Perú. http://www.beyondthemine.com/pdf/CRRYanacocha-Spanish-FINAL.pdf

- Fernández-Jáuregui, C. 1999. El Agua como fuente de conflictos: Repaso de los Focos de Conflictos en el Mundo. Afers Internacionals, núm. 45-46, pp. 179-194 (Fundació CIDOB). http://www.raco.cat/index.php/revistacidob/article/viewFile/28132/27966

- Guevara, A. 2008. Derechos y Conflictos de agua en el Perú.

- Knight Piesold Consultores S.A. 2010. Resumen ejecutivo del Estudio de Impacto Ambiental del Proyecto Conga.

- Ministerio del Ambiente. 2011. Informe N°001-2011 Comentarios al Estudio de Impacto Ambiental del proyecto Conga, aprobado en octubre de 2010.

- PNUMA (UNEP). 2010. El Enverdecimiento del Derecho del Agua: la Gestión de los Recursos Hídricos para los Seres Humanos y el Medio Ambiente.

- Rubio, R; García, L. y Carvalho, J. 2012. Dictamen Pericial Internacional Componente Hídrico del Estudio de Impacto Ambiental del Proyecto Minero Conga.

- WordPress.com. Blog Celendin Libre. Pronunciamiento: ONG Oxfam se pronuncia respecto a caso Minas Conga. http://celendinlibre.wordpress.com/2012/04/17/pronunciamiento-ong-oxfam-se-pronuncia-respecto-a-caso-minas-conga/

- Yanacocha. 2010. http://www.yanacocha.com.pe

[2] Minera Yanacocha is named after the ancient Yanacocha lagoon, on which its first gold mine developed.

[1] Falkenmark indicator measures the availability of water per person and indicates the level of sustainability of the resource for a country. Values below 1000 m3/capita indicate “water stress”; between 1000 and 2000 m3/capita is considered critical and over 2000 indicate an acceptable threshold for sustainable development.

Pingback: EIA Process in Peru: Overlooking Public Participation in the Minas Conga Gold Mine Project | Environmental Assessment